Image by exdez / DigitalVision Vectors via Getty Images

UBC’s contributions to combatting COVID-19

Look back at some of the UBC Faculty of Medicine’s efforts that contributed to our ongoing pandemic response and recovery.

By Craig Takeuchi

Do you remember videos that visualized clouds of droplets spreading out in the air after someone coughs or sneezes? Or arrows directing which way to walk down aisles in stores? Or reading daily updates about ever-rising COVID-19 case counts?

All of those things marked the early phases of the pandemic, which the World Health Organization officially declared on March 11, 2020. But headlines about COVID-19, which once saturated the news, have significantly decreased in number.

Since the pandemic began, Canada has had more than four million cases and over 50,000 deaths. Worldwide, we’ve had approximately 700 million cases and about seven million deaths. That’s not to mention the immeasurable impacts that the pandemic has had on physical and mental health, relationships, healthcare, livelihoods, economies, global systems, and more.

Although COVID-19 may still be with us, we’ve significantly advanced since those initial periods of lockdowns, fear, and confusion. To appreciate how far we’ve progressed, here’s a roundup of some notable contributions that UBC faculty, alumni, students, and staff have made in helping us find our way through periods of great uncertainty to get to where we are today.

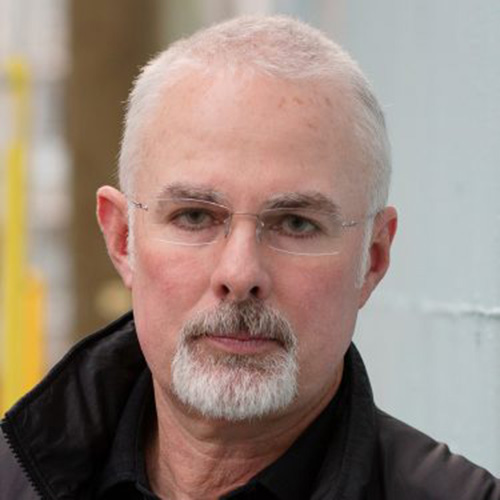

Dr. Roger Wong

Compassion in action

While UBC may be associated with intellect, many of its community members responded to the COVID-19 crisis not only with their heads but also their hearts.

Everyone struggled with social restrictions, but seniors in long-term care facilities were completely cut off from their personal relationships. To help mitigate this concerning situation, Dr. Roger Wong, a clinical professor of geriatric medicine in the Faculty of Medicine, led the Connecting with Compassion initiative (thanks to generosity from Dr. Edwin S.H. Leong) to deliver iPads so that care facility residents could virtually reconnect with their family and friends, as well as with UBC medical students who volunteered their time. For a recreational boost, the tablets included recorded performances by UBC School of Music students.

Early on in the pandemic, UBC clinical instructor and Kelowna General Hospital emergency physician Dr. Tony Kwan recognized the need to educate discharged COVID patients with developing information about self-isolation. He recruited UBC emergency medicine residents and Southern Medical Program student volunteers from UBC Okanagan to follow up with these patients by phone to address challenges such as preventing transmission within homes, obtaining groceries and prescriptions, and other pressing concerns.

With many rural and remote Indigenous communities in B.C. under lockdowns to prevent transmission, healthcare access became a challenge. The solution? In 2021, the Faculty of Medicine collaborated with the Stellat’en First Nation and the Village of Fraser Lake in northern B.C. on a pilot project using drones to deliver healthcare supplies like personal protective equipment, medications, and tests.

Among the sectors impacted by B.C.’s COVID-19 restrictions were faith services and places of worship, including gurdwaras, or Sikh temples. UBC medical student Sukhmeet Sachal led the Sikh Health Foundation Initiative, which used culturally-specific means to convey public health information to Sikh communities. Volunteers helped distribute masks (with ties behind the head, as turbans cover ears) while teaching people how to wear them.

When B.C. declared a public health emergency on March 18, 2020, 10 students from UBC’s Peter A. Allard School of Law were in the midst of providing free legal services at the Indigenous Community Legal Clinic, an experiential learning program in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. At that point, wrapping up the semester prematurely would have been the safest and simplest thing to do. But the team refused to leave their clients in the lurch and instead chose to forge on, taking home approximately 150 files to continue on with their work by remote means.

Dr. Anna Blakney

In the know

Concurrent with the pandemic was the infodemic, the explosion of ever-evolving COVID-19 information, misinformation, and disinformation from all directions, including from health experts, politicians, public figures, celebrities, influencers, dubious sources, and even friends and family.

Like many post-secondary institutions, UBC became one source that the media consistently relied upon for interviews with professors and researchers. Numerous UBC experts covered a diverse range of topics, from pregnancy concerns and children’s health issues to racist blaming of demographic groups to shifts in sexual behaviour.

With fortuitous timing, psychiatry professor and clinical psychologist Dr. Steven Taylor had his book The Psychology of Pandemics: Preparing for the Next Global Outbreak of Infectious Disease published one year before the pandemic hit. Not only was he frequently interviewed in the media but he also became a member of the Canadian federal government’s expert panel on COVID-19, and a co-leader of the Psychology of Pandemics Network, consisting of mental health scientists, clinicians, and trainees from universities across Canada and the U.S.

When it came to COVID-19 and pregnancy, there was a lot the world didn’t know. The Faculty of Medicine’s Reproductive Infectious Diseases Program, led by Dr. Deborah Money, sought to fill that knowledge gap. They initiated a national surveillance study, CANCOVID-Preg, that tracked maternal and infant outcomes among pregnant people with COVID-19. The project showed that pregnant people were at greater risk of being hospitalized, admitted to ICU and going into early labour. The team also launched a COVID-19 vaccine registry for pregnant and breastfeeding individuals in Canada to monitor the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines in real time. The team’s work has been widely influential in informing clinical and public health guidelines, vaccine recommendations and maternal and newborn care throughout the pandemic.

Health professionals and scientists also took to social media to combat the endless flow of misinformation. Among them was Dr. Anna Blakney, an assistant professor at the School of Biomedical Engineering and UBC’s Michael Smith Laboratories who researches mRNA technology. Dr. Blakney joined the campaign Team Halo, in which doctors and scientists involved in the vaccine effort used social media to address vaccine hesitancy and confusion.

Interestingly, media coverage of how modelling could be used to chart our way through pandemic waves shone a spotlight on math. One frequently quoted UBC expert was Mathematics professor Daniel Coombs, who was part of the B.C. COVID-19 Modelling Group, which worked independently from the provincial government.

Most prominently, one UBC professor took on the intense challenge of keeping British Columbians informed about COVID-19 while steering the province through one of the most difficult periods in its history. B.C. Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry, who is also a clinical associate professor at UBC’s School of Population and Public Health, led B.C.’s pandemic response and continually provided COVID-19 updates alongside B.C. Health Minister Adrian Dix. She synthesized medical and scientific information, including epidemiology and modelling, into language that the average person could understand. Her calm demeanour, empathetic leadership, and science-based approach garnered praise. Over time, she faced growing criticism from all sides — including extremist responses, involving threats of harm or death. Despite all of this, Dr. Henry bravely persevered and continues on. In the spring of 2021, she received an honorary Doctor of Science degree from UBC.

Dr. Sriram Subramaniam (right) with a microscope used to take pictures at near-atomic resolution. The microscopes measure up to 13 feet in height, as tall as a double decker bus.

Deep dives

A research team, led by Dr. Sriram Subramaniam, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology in the Faculty of Medicine, made several significant breakthroughs by using massive microscopes — up to 13 feet tall. Using cryo-electron microscopy, the team captured images of the COVID-19 spike protein at near-atomic resolution to assess the binding of different antibody treatments to the virus. By September 2020, the researchers determined that antibody-based drug Ab8 prevented and neutralized the virus.

Then in May 2021, the team became the first in the world to publish structural images of the Alpha (B.1.1.7) variant spike protein. Marking yet another worldwide first, the team also conducted a molecular-level structural analysis of the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant spike protein. The results, published in December 2021, revealed how the highly contagious variant (which emerged in November 2021 with an unprecedented 37 spike protein mutations) evaded immunity and infected human cells. By determining the structures of the proteins, the researchers laid the groundwork for the design of medication and vaccines. (There’s more to come from Dr. Subramaniam later on.)

When mass testing centres closed down as testing shifted to home kits, new means were needed to monitor the spread of COVID-19 amongst populations. One option was wastewater surveillance. UBC professor Dr. Ryan Ziels, who is an environmental engineering researcher focussing on microbial ecology, led an analysis of sewage samples from five wastewater plants in Metro Vancouver from February to April 2021. The results, posted in May 2021, revealed viral concentrations in wastewater collected from the Vancouver region were consistent with case numbers in the region. These findings helped confirm that wastewater testing could accurately identify COVID-19 infections (and variants), which is what B.C. has been increasingly using in tracking COVID-19. In January 2023, for instance, the B.C. Centre for Disease Control expanded its wastewater testing program from the Lower Mainland to Vancouver Island and the B.C. Interior.

Dr. Pieter Cullis

Protection and prevention

One of the most significant game-changers in the worldwide battle against the novel coronavirus came from UBC Faculty of Medicine professor Dr. Pieter Cullis. For decades, this internationally renowned scientist pioneered work in developing microscopic lipid bubbles — a novel drug delivery system — which enabled Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna to create mRNA vaccines effective against COVID-19. This lipid nanoparticle technology was developed by Acuitas Therapeutics, a UBC spinoff biotech company co-founded by Dr. Cullis. Needless to say, the vaccines are what enabled countries and regions to lift lockdowns and ease restrictions, allowing us to regain greater freedom and mobility. Among the numerous accolades and praise from around the world that Dr. Cullis has garnered was Canada’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize: the annual Canada Gairdner Award.

Personal protective equipment became a household word during the pandemic — but also generated massive waste streams.

At UBC’s Point Grey campus, Melody Salehzadeh, a doctoral student in the department of zoology, became concerned about the huge amounts of nitrile and latex gloves going into the garbage at her lab. The AMS Sustainability Project and the UBC Student Environment Centre provided funding for Salehzadeh and her team to buy two large pallets to collect the gloves. By August 2022, the project had collected approximately 48,700 gloves, thereby diverting 146.1 kilograms of waste from landfills. Inspired by this project, managers at the UBC Centre for Disease Modelling, the Modified Barrier Facility, and the Centre for Comparative Medicine launched recycling initiatives to collect disposable gloves, masks, shoe covers, hair bouffants, and more.

Tackling this issue in a different way, UBC’s BioProducts Institute announced in May 2020 that its researchers designed one of the world’s first compostable and biodegradable N95 medical masks, dubbed the Canadian-Mask or Can-Mask. Using B.C. wood fibres, this mask could be sourced and manufactured entirely in Canada, which was an important consideration amid worldwide supply chain instability and disruptions.

Meanwhile, several disinfection innovations developed in response to the pandemic can be used to battle more than just COVID-19.

Engineering alum Kunal Sethi and his colleague Saimir Sulaj co-founded the Vancouver-based startup UVX which created Zener, a ceiling-mounted device that disinfects surfaces and the air. It uses a far-UVC light, an ultraviolet light of a specific wavelength, that destroys germs without harming humans. As it can kill various pathogens, this device has applications beyond eliminating SARS-CoV-2.

In January 2022, UBC researchers published a study about their development of a non-toxic coating that reduces the infectious ability of the COVID-19 virus by up to 90 per cent. The inexpensively made coating (requiring a polymer solution and ultraviolet light) kills bacteria such as E. coli and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) on contact (sunlight exposure augments its bacteria-zapping ability). This coating can be applied to fabrics, including masks, hospital fabrics, and activewear.

Cryo-electron microscopy reveals how the VH Ab6 antibody fragment (red) attaches to the vulnerable site on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (grey) to block the virus from binding with the human ACE2 cell receptor (blue). Credit: Dr. Sriram Subramaniam

Ensuring an endgame

In August 2022, the previously mentioned Dr. Subramaniam and his UBC research team helped make another significant discovery. In collaboration with the University of Pittsburgh, the researchers published the identification of a crucial susceptible spot consistent in all major variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Neutralizing antibodies could be used to target this vulnerability, which could thereby be used in treatments effective for all variants.

Another team of UBC researchers, led by the Faculty of Medicine’s Dr. Natalie Strynadka and Dr. Artem Cherkasov, has contributed to the development of next-generation anti-viral drugs to treat COVID-19. They employed cutting-edge techniques, like artificial intelligence and X-ray crystallography, to understand how the coronavirus replicates, and importantly, how to stop it from replicating. This approach has been successfully used to develop drug treatments for other viruses such as HIV.

UBC researchers have also identified several compounds to combat COVID. In December 2022, Faculty of Medicine researchers at UBC’s Life Sciences Institute published findings about a compound that could potentially be used in antiviral treatments for coronaviruses, ranging from SARS-CoV-2 to the common cold. This compound could be used for both current and future pandemics.

Then in January 2023, scientists found three compounds that prevent COVID-19 infection in humans. After investigating more than 350 compounds, the UBC–led international research team discovered that the most effective compounds were derived from natural Canadian aquatic sources: alotaketal C, from a sea sponge in Howe Sound, B.C.; bafilomycin D, from a marine bacteria in Barkley Sound, B.C.; and holyrine A, from marine bacteria from Newfoundland.

All of these efforts contribute to our collective advancement in the battle against the highly adaptable and evasive virus that has deeply impacted almost all aspects of our world over the past three years. While future complications remain a possibility (such as new variants arising or vaccine efficacy waning), we all can take stock of how much the UBC community has accomplished — as the world continues to work towards ending this pandemic.

A version of this article was originally published by The University of British Columbia Magazine.