Scientists from UBC’s faculty of medicine and the Institute of Molecular Biology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (IMBA) have discovered that the gene, known as JAGN1, plays an important role in antibody production and the body’s ability to mount a defense against pathogens, including viruses.

The findings were published online today in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Dr. Josef Penninger

“Antibodies play a fundamental role in medicine, and antibody-mediated immune response is the ultimate target in the quest for a vaccine to defeat the current pandemic,” says the study’s senior author Dr. Josef Penninger, a professor in the department of medical genetics and director of the Life Sciences Institute at UBC and a researcher at IMBA.

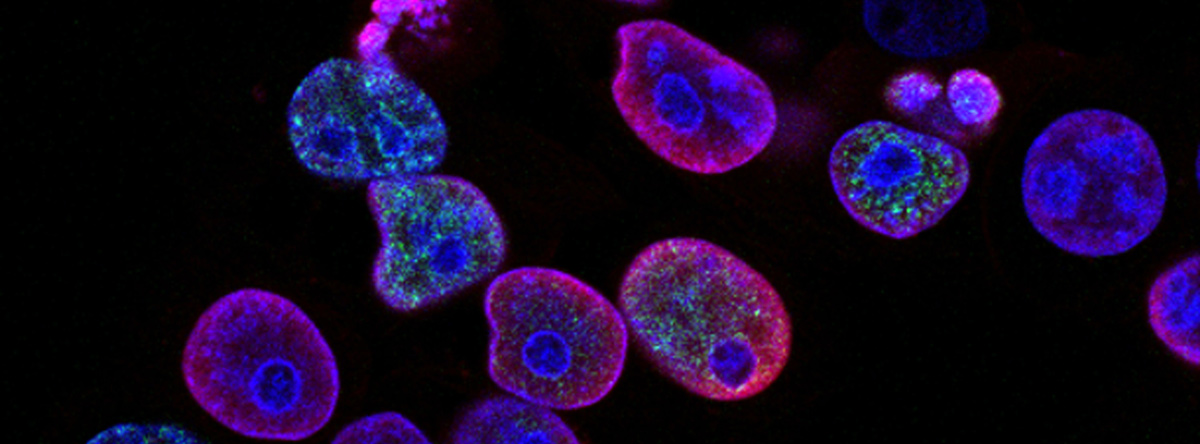

As part of their investigation, Dr. Penninger’s research groups at UBC and IMBA shed light on the role of JAGN1 in relation to B cells, which are white blood cells that can develop into plasma cells when they recognize foreign substances, such as chemicals, bacteria, viruses and pollen. In their plasma cell form, B cells can produce thousands of antibodies per second that target a specific intruder. This production occurs at a location within the cell known as the endoplasmic reticulum.

“When we knocked out JAGN1 in B cells of mice, we were able to measure a drastic reduction in the number of antibodies,” says the study’s first author Dr. Astrid Hagelkruys, a senior research associate at IMBA.

The researchers also found that the altered sugar molecules, which coat antibodies, facilitate an antibody’s ability to bind to other immune cells, thereby strengthening the body’s defensive reaction.

“JAGN1 seems to influence the antibody factories in the cells,” says Dr. Penninger. “To our surprise, this change in the sugar structure also leads to a better ability of the antibodies to bind to other immune cells and strengthens the defense reaction.”

The scientists were able to demonstrate this mechanism in human samples.

“Rare genetic defects occur in only a handful of people, but they can sometimes help us decipher basic principles of biology,” adds Dr. Penninger. “In this case, we were able to prove that a certain gene affects the endoplasmic reticulum and is therefore essential for the mass production of antibodies.”

The gene JAGN1 had been previously identified as a player in the body’s immune system by the Penninger lab in collaboration with the Klein lab at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich among patients with severe congenital neutropenia (SCN)—a disease caused by a mutation in the JAGN1 gene. Patients with SCN have abnormally low levels of white blood cells called neutrophils, and suffer from serious infections because their immune systems cannot effectively kill off bacterial or fungal invaders.