A series of experiments on fruit flies suggests that differences between men and women in the development of heart disease and diabetes may be influenced by differences in their insulin secretion.

Fruit flies provide a convenient window into the molecular basis for sex differences because they don’t have sex hormones, and both males and females exhibit identical feeding behaviour during development. Yet females grow to be 30 percent larger than males.

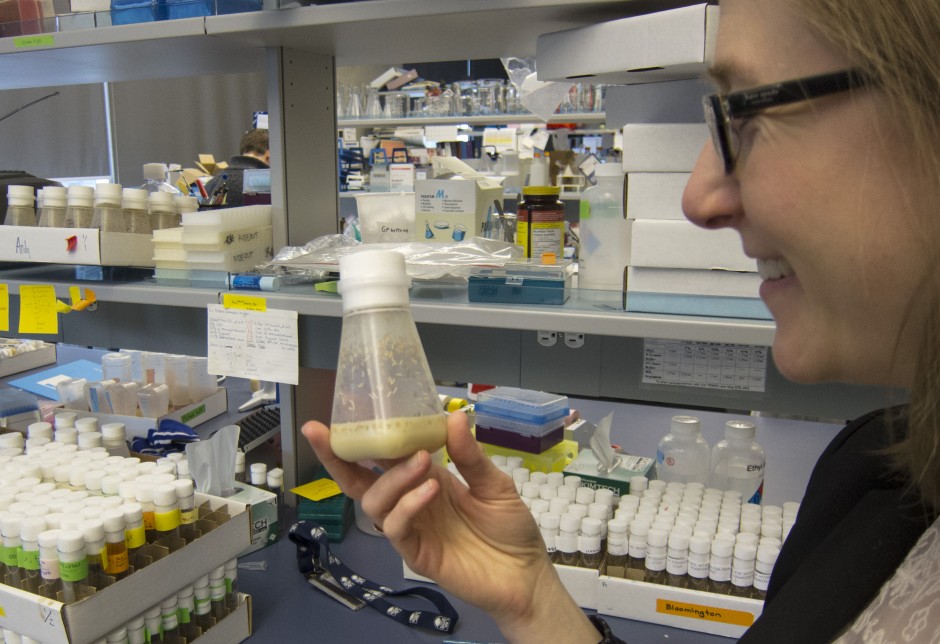

Elizabeth Rideout, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, decided to find out why, focusing on a gene known as tra (short for transformer), which is expressed only in cells of female fruit flies. When she bred female fruit flies whose tra gene was silenced, Dr. Rideout found that the mutant females were only 10 per cent larger than males. Conversely, when she forced tra gene expression in males, the males grew to be larger than normal males.

Subsequent experiments demonstrated that the tra gene affects body size by increasing the secretion of fly insulin, which, like insulin in all animals, stimulates tissue growth – thus leading to female fruit flies’ larger size.

Dr. Rideout’s work, published in December in PLoS Genetics, have broad implications for understanding differences between the sexes in other animals, including humans. Although the sex of humans is determined differently than it is in fruit flies, the downstream mechanisms that affect body size – including the insulin pathway – are very similar.

The findings also can help explain differences in metabolic diseases between men and women, since changes to insulin secretion affects the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes – both of which affect more men than women.

“Difference in health outcomes between men and women are influenced by all sorts of factors, including sex hormones, body composition, behavior and diet,” says Dr. Rideout, a member of the Life Sciences Institute. “But the sex of individual cells, independently of sex hormones, also plays a critical role in disease. If we can uncover the fundamental differences between male and female cells using flies as a model, in the future we can develop drugs to protect the at-risk sex – in some cases, men, and in other cases, women – from disease.”