Students at the Eaton Arrowsmith School doing the clocks task. Photo courtesy of Eaton Arrowsmith School

Lara Boyd explores whether an unorthodox curriculum has a neurological impact on children

It doesn’t take long to discern that the Eaton Arrowsmith School takes a distinctive approach to education.

Most of the time, students work quietly by themselves, on what appear to be tedious tasks: tracing ornate, unfamiliar letters from Chinese, Urdu or Burmese, often while wearing eye patches; listening to recorded phrases, and repeating them from memory, word-for-word; looking at images of clocks that flash on their screens, and typing in the displayed time – except the clocks can have as many as 10 hands, and the answers sometimes include identifying the correct millennium.

The school, based in rented space on UBC’s campus, caters to students with learning disabilities. Its curriculum amounts to physical therapy for the brain.

The founder, Howard Eaton, adopted the approach from the Arrowsmith Schools in Ontario, founded by Barbara Arrowsmith-Young. Both Eaton and Arrowsmith-Young believe that children can overcome learning disabilities through specific cognitive exercises – if done repeatedly, at increasing levels of difficulty, with ever-increasing speed and accuracy. They assert that such a regimen re-wires children’s brains so that, after a couple of years, students can hold their own, even thrive, in conventional schools.

Scores of parents, who pay $29,000 a year for a full-time slot at Eaton Arrowsmith, believe in it. A handful of Canadian and U.S. private schools have adopted the program for some of their students, and a second Eaton Arrowsmith school opened in September in Redmond, Washington. But this unconventional approach, and the bold claims that underlie it, have yet to be accepted by the education establishment – something that has nagged at Eaton since he founded the school in 2009.

Now, the Faculty of Medicine has begun an unprecedented effort to see if those claims can be verified.

From studying stroke to studying students

The effort is led by Lara Boyd, an Associate Professor of Physical Therapy and Canada Research Chair in the Neurobiology of Motor Learning. Dr. Boyd’s specialty is recovery from stroke – specifically, how the brain adapts to damage caused by a lack of blood flow to the brain, and how it can re-learn tasks, or even basic functions, in the process.

Dr. Boyd has a wealth of experience imaging the brains of older people. She has never worked with children.

“I’m not in education,” she says. “But I can determine whether someone’s brain has changed, and what behavioural changes correlate with those changes. I was intrigued by this project conceptually, and think it’s worth investigating.”

The project is being funded by private donations, including $105,000 from Eaton and $107,527 from the family of Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella (whose child attended the Eaton Arrowsmith School in Vancouver and is now attending the one in Redmond).

But Dr. Boyd has made one thing clear: She wants to publish whatever she finds, because the results would have major implications for the field of neuroplasticity – the ability of the brain to change, either at the cellular level or through the remapping of its signaling pathways.

“In rehabilitation, we’ve been very hot on plasticity,” says Dr. Boyd, a member of the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health. “Can we pump up the brain, make it stronger through practice, so a person can achieve the same thing but in a different way? No one in my field would question that. But the notion of having enough brain matter to learn something is a very novel concept in education.”

Looking at the cortex, myelin and oxygen consumption

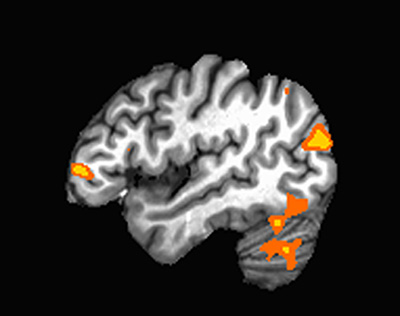

Dr. Boyd will be one of the first scientists to try to answer this question in children, by examining the brains and cognitive performance of Eaton Arrowsmith students between 9 and 17 years old, at two points in time, a year apart. She will also compare those results with a control group of learning-disabled students who are not in the school and are receiving assistance in public schools or other private schools. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), she will be trying to answer these questions:

- Do the cortices (the outermost layer of the brain) of Eaton Arrrowsmith students become thicker? This would indicate an increase in dendrites – the branches of neurons that receive signals from other neurons.

- Do the students have more myelin surrounding their neurons? A thicker amount of that insulating material allows impulses to travel more quickly through the neuron, thus enabling quicker responses by the brain.

- Do the students’ brains use less oxygen during the clocks task? This would indicate that their brains have become more efficient.

Dr. Boyd’s project will also put the students through a battery of cognitive tests, assessing the students’ short-term memory, attention levels and intellectual abilities, looking to

see if any changes in brain tissue and activity correlate with behaviour.

Eaton, whose own struggles with dyslexia as a UBC student led to a very public battle to be exempted from the university’s foreign language requirement, is confident that the study will vindicate his schools’ approach. If that happens, he hopes public schools would adopt it for students who need it, so parents won’t have to spend $29,000 a year at his school.

“We have kids working six hours a day on cognitive exercises, for 10 months out of the year,” he says. “I might be overly optimistic about it, but brain change is inevitable. The question is where, how and why, and how is the change benefiting kids’ academic and social lives?”