The list of must-have items for parents of newborns has remained pretty much the same for decades: sleepwear, blanket, car seat, and of course, diapers and wipes.

B.C. parents are now starting to have one more item included in that list: an easy-reference card for examining the colour of their newborn’s stool.

While parents may not welcome the reminder of how many diaper-changings await them, the card – spearheaded by Clinical Professor of Pediatrics Rick Schreiber – may very well alert them to a rare, life-threatening condition that can only be corrected with surgery.

The condition, biliary atresia, is a blockage of the bile duct, the main draining pipe for eliminating bile and other toxic substances from the liver. Left untreated, it leads to liver failure within the first two years of life.

Timing is everything

Most children with biliary atresia now survive. A liver transplant is the last-ditch option, but carries all of the complications and risks that any transplant procedure entails, compounded by the age of the patient. A safer and less costly procedure is the creation of a bypass conduit that re-establishes flow from the liver to the bowel.

Known as a Kasai portoenterostomy (named for the Japanese surgeon who invented it), the procedure became widely available in the 1980s. But its effectiveness depends on when it’s done. If performed in the first two months of life, it has a 60 per cent to 80 per cent chance of success; after three months, that success rate drops to 20 per cent.

So detecting the condition quickly is the key to avoiding a transplant. And that is a challenge.

There is no blood test for biliary atresia. Jaundice (a yellow tinge to the skin and eyes) is a symptom, but it’s often dismissed by parents – and doctors – because most cases of jaundice are temporary and clear up on their own. Moreover, most Canadian babies don’t have their first check-up until they are two months old.

“We – not just in Canada, but everywhere – were having too many late referrals,” Dr. Schreiber says. “It’s a rare disease, so most doctors don’t see a single case in their whole careers. It’s like looking for a yellow needle in a yellow haystack.”

That is where poop comes in.

Borrowing from Taiwan

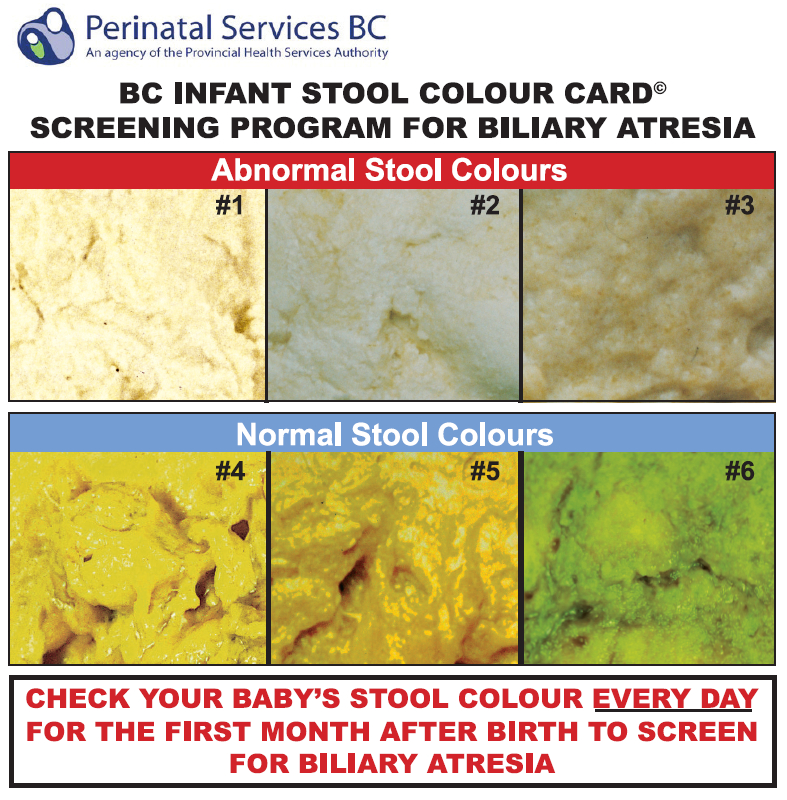

Biliary atresia causes a baby’s stool to be pale-coloured or chalk-white rather than the normal golden yellow or dark green. And a baby’s parents are the ones most likely to notice the abnormal colour.

Dr. Schreiber, the Director of the B.C. Pediatric Liver Transplant Program, borrowed the idea of a colour card from Taiwan, which pioneered it a decade ago; as a result, the country managed to detect nearly all cases of biliary atresia before 90 days. The card contains photos of abnormal and normal infant feces and directions to check the colour of their baby’s stool every day.

Dr. Schreiber teamed up with fellow pediatric specialists, family medicine researchers and health economists at academic medical centres across Canada, and obtained funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to conduct a pilot of the colour card in B.C. (in Vancouver and Prince George) and Quebec. They tested various tactics in tandem with the cards – reminder cards mailed to parents, phone call reminders, letters to newborns’ family doctors, phone calls to those doctors.

The most cost-effective strategy, they found, was simply providing the card to parents when the baby was discharged from hospital. Based on their calculations, a B.C.-wide program would save $5 million over a decade, and spare about 15 to 20 children and their families the risk, pain and anxiety of a liver transplant during that period.

After reviewing the results of the pilot study, Perinatal Services BC (an agency of the Provincial Health Services Authority) and its Oversight Council decided to make the cards a part of every newborn discharge procedure.

Leading the way

“This initiative is a great example of how we’re leading health care innovation in British Columbia,” says Kim Williams, Provincial Executive Director of Perinatal Services BC. “Even something as simple and low-tech as the stool colour cards can make a significant difference in the outcomes of newborns. This at-home screening program will reduce the need for liver transplantation and improve the overall survival of these tiny patients.”

The card includes directions to contact Perinatal Services BC for follow up if their newborn’s stool colour looks abnormal. (More information is available at http://bit.ly/biliary_atresia.)

Distribution of the cards to maternity hospitals began this summer, with the entire province expected to be covered in the next year – the first province in Canada, and one of the only jurisdictions in the world, to do so. The cards also will be distributed to midwives, who will give the cards to their clients after delivery at clinics or the parents’ homes.

“Once we get things going here, we’ll look at rolling it out in Quebec, and then, we hope, the rest of the country,” Dr. Schreiber says.

He and his colleagues have also established a biliary atresia national registry to track every Canadian child who has the condition; the disease is so rare that provincial statistics are inadequate.

“So we’ll be able to measure the effectiveness of a colour card in one province, compared to a province that doesn’t have one,” he says. “We might also be able to detect if some provinces have better outcomes for the Kasai procedure than others, and then try to pinpoint the reasons.”