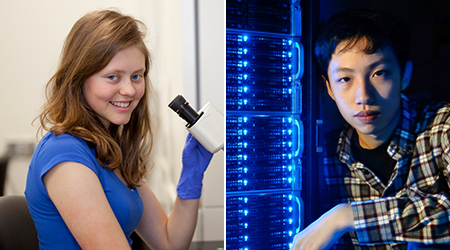

When Allen Zhang entered the Faculty of Medicine in August 2013, he had the distinction — unbeknownst to him — of being the youngest student ever to enrol in UBC’s medical program.

Then, a year later, Leah Kosyakovsky came along.

Kosyakovsky, all of 16 years old, joined the newest contingent of 288 first-year medical students in August, after having earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Minnesota in May and being accepted to two other Canadian medical schools.

Typically, students enrol in medical school in their early 20s after spending four years at university, and sometimes pursuing other interests, other degrees or even careers. Zhang and Kosyakovsky, having proven their academic mettle and becoming certain of what interested them, saw no need to wait.

“I have a happy personality and tend to like everything I do, so even if I’m intimidated by older classmates, I end up enjoying being with people who have done more things than I have,” she says.

Zhang, who entered the medical program last fall at the age of 18, is similarly unfazed by the age difference separating him and his classmates – so unfazed, in fact, that he applied for the especially demanding MD/PhD program last spring so he could combine his love of computer science with his interest in health science. When he was accepted, he also became the youngest student to enter that program, which typically lasts seven years.

“He makes numbers dance,” says one of his co-supervisors, Wyeth Wasserman, a Professor of Medical Genetics and Director of the Child & Family Research Institute.

Kosyakovsky, too, has a strong interest in research. As an undergraduate in Minnesota, she joined the lab of biochemist Reuben Harris, and embarked on a project of her own choosing: Why the gene APOBEC3B sometimes become over-expressed, leading to cancer-causing mutations. Her work in the lab will earn her co-author status on a paper that Dr. Harris is working on.

“She has stratospheric potential,” Dr. Harris says. “If she’s starting with this level of energy and understanding, the sky’s the limit.”

All-around excellence

Like the rest of the MD class, Zhang and Kosyakovsky were not admitted solely on the basis of their grades and test scores. They also demonstrated their versatility, an ability to work well in groups, and well-roundedness in non-academic areas – Zhang, a violinist, recorded two violin CDs and busked on Granville Island, while Kosyakovsky was a prize-winner at a U.S. national tae kwon do competition.

“Just to be considered for an interview, you have to have done a lot,” says Bruce Fleming, the Associate Dean, Admissions.

Then they had to display maturity, thoughtfulness and a solid sense of ethics in interviews, which are granted to 640 of the 2,100 annual applicants.

Their acceptance isn’t just a coup for each of them. Their youth, Dr. Fleming says, contributes to the diversity of the MD class, and thus is a boon to the other students.

“We try hard to include applicants from non-traditional backgrounds,” Dr. Fleming says. “We don’t want to take a cookie-cutter approach. A large part of our program’s strength stems from the diversity of our students, whether it’s their ethnic backgrounds, talents, academic interests, or age.”

Zhang’s and Kosyakovsky’s attributes were so outstanding, regardless of their age, that Dr. Fleming says UBC didn’t want to lose them to another medical school. Moreover, the Faculty of Medicine’s policy forbids discrimination – even in admissions – on the basis of age.

An infinite number of “why’s”

Kosyakovsky grew up in a small town 30 kilometres east of St. Paul, Minnesota. She started reading at 3, entered kindergarten a year early, then skipped the second grade.

“She was always asking ‘why,’” her father, Boris recalls. “‘Why is the grass green?’ ‘Why is the sky blue?’ ‘Why are there so many stars when the sky is dark?’ An infinite number of ‘why’s.”

In the seventh grade, she entered an accelerated math program run by the University of Minnesota, taught by university professors.

Isaac Asimov’s writing sparked her interest in science – not his science fiction, but the real science. Her favourite parts were his explanations of biology.

“I was always amazed by the complexity of living organisms,” she says. “I was always surprised by how it came to be in the first place.”

And from that amazement sprung her aspiration to become a doctor.

“Once you realize how amazing it is that you’re here in the first place, you want to be able to make the most of your life,” she says. “I also wanted to do something that had the potential for lifelong learning, and I realized that as a physician, I would be able to have a very fulfilling life.”

In the 11th grade, she entered a program that allows high school students to take university courses for both secondary school and university. But she found herself barred from upper-level biochemistry courses because she wasn’t an official student majoring in science. So she graduated from high school a year early, and enroled at university.

By getting credit through Advanced Placement tests and taking 20 credits a semester at the University of Minnesota, all it took was another year to earn a bachelor’s degree.

Kosyakovsky is a permanent resident of Canada, thanks to her parents and siblings having moved to Alberta several years ago; she stayed behind, with her grandparents, because her parents decided the accelerated program was too good an opportunity. While UBC reserves most of its medical school seats for B.C. residents, it admits a few individuals every year from other parts of Canada.

But Kosyakovsky is already familiar with UBC, thanks to visits to her older sister while she was earning a nursing degree here.

Dissecting fish at age 10

Zhang, meanwhile, has a long history with UBC. He started to learn his way around at the age of 10, while visiting UBC’s Biology Department, where his mother works as a lab technician.

“My co-workers showed him how to dissect fish, and to look under the microscope at different organisms,” Xueqin Huang says. “Some students are afraid to open the fish’s heart, but he loved it.”

He became even more familiar with UBC when he was accepted into the University Transition Program at 13. Transition students pursue an accelerated academic curriculum, including some university classes, and earn their high school degree two to three years earlier than their peers in conventional schools.

Allen Zhang (centre) speaks with his PhD co-supervisors, Sohrab Shah (left) and Wyeth Wasserman. Photo credit: Don Erhardt

Thanks to the Transitions program, he entered UBC at 15, and despite his youth, was admitted to Science One, a first-year undergraduate course that covers biology, chemistry, mathematics and physics in a unified format that fulfills second-year prerequisite requirements for all of those subjects.

“Some students will be strong in one discipline but not so strong in one or two others,” recalls one of his instructors, Associate Professor of Mathematics Eric Cytrynbaum. “Allen had the opposite problem. He was interested and adept in several disciplines. I remember him being especially intrigued that some researchers don’t tie themselves down to a single discipline.”

Even though it took a while for Dr. Cytrynbaum to realize Zhang was three years younger than his classmates, Zhang distinguished himself in other ways.

“Allen was one of those students who become aware, very early on, that their instructors don’t know everything – that there are questions that go beyond what is said in class,” he says. “I think it was exciting for him to find those questions.”

Swimming in the deep end

Outside of class, Zhang spent three months in a wet lab, but realized he was more comfortable with numbers than pipettes. In his second year, he joined Dr. Wasserman’s lab, which specializes in computational genomics.

“We would give him a task that we expected an undergraduate to work on for two or three weeks, and Allen would come back the next day with the task completed,” Dr. Wasserman says. “It was a challenge just feeding him projects that were hard enough and robust enough to stretch his talents. So we decided to throw him in the deep end, cancer genomes – specifically, figuring out when certain mutations begin to express themselves.”

Once again, Zhang’s youth was not apparent. It didn’t dawn on Dr. Wasserman until the lab prepared to celebrate the graduation of one of its members at Mahoney’s, and Zhang had to decline an invitation because he was under – way under – the legal drinking age.

Zhang’s parents encouraged him to apply to medical school a year early – not with any real hope of being admitted, but just to become familiar with the application process. When he surprised himself by getting admitted, Dr. Wasserman not only encouraged him to apply to the MD-PhD program but met with the program’s directors to allay their concerns about his lack of a bachelor’s degree.

Zhang, who is being co-supervised by Sohrab Shah, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, will focus on making predictions about the course of a patient’s cancer that could inform decisions about the most effective therapy. He will most likely focus on ovarian cancer, picking out cases that would be suitable for studies and building data sets that would allow patterns to emerge.

The combined program takes seven years, so by the time he is done, Zhang will be closer in age to (but still a bit younger) than most newly-minted MDs.

“I’ll probably try to split my time between clinical work and research,” Zhang predicts. “I’m just not sure what kind of patients.”