Back in the early 1990s, Rowena Dagley was so fast a runner at Nanaimo’s Wellington Secondary School that the boys track coach recruited her for his squad – only to see her running career cut short by severe pain in her Achilles tendon.

That was just about the time that she discovered, in the course of having her blood tested for other ailments, that she had very high cholesterol, inherited from her mother.

Until this year, she had never associated the two conditions. Nor did any of her doctors.

But LDL can inflict another type of damage: tendon xanthomas.

The yellowish deposits result from LDL accumulating in tendons, similar to the way it builds up in blood vessels. Due to the biochemical affinity between LDL and the collagen found in tendons, LDL escapes from the bloodstream and attaches to tendons, particularly the Achilles, becoming ever larger and harder, and causing inflammation that ultimately undermines the tendon’s structural integrity.

“Tendon xanthomas can be pretty disabling, making it painful just to walk around,” says Alex Scott, an Associate Professor of Physical Therapy who has been studying tendons for a decade.

One diagnosis leads to another

Not surprisingly, xanthomas commonly occur in people with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) – inherited high cholesterol. The two conditions are so well correlated that a diagnosis of xanthoma, when it does occur, often leads upon further examination to a diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia.

But xanthomas are often misdiagnosed as purely a tendon issue resulting from overuse or aging, leading to ineffective treatment with anti-inflammatory medication. And because xanthomas aren’t as life-threatening as heart disease or stroke, there has been little effort to understand exactly what they are doing to tendons, and whether they require a different kind of treatment.

Dr. Scott and postdoctoral fellow Charlie Waugh are trying to remedy that situation by doing the first-ever investigation of tendon health in people with inherited high cholesterol.

Dagley, one of the participants in the study, was recruited from a registry of people with FH that was started by UBC’s Jiri Frohlich, and which has since expanded into a national database. That was how she first learned that the occasional flare-up of pain in her Achilles tendon could very well be another consequence of her high cholesterol.

“I knew cholesterol builds up in certain parts of your body, but I didn’t make the connection,” says Dagley, a restaurant server.

Treadmill work

About once a week, someone like Dagley comes to the Mobility Function Lab at Vancouver General Hospital to walk, run and jump on a specialized treadmill – part of a small, pilot study funded by a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions Fellowship from the European Commission.

A magnetic resonance image of a thickened tendon resulting from a xanthoma. Reprinted from Academic Radiology, Vol. 2 No. 4, Terhi Koivunen-Niemela et. al., 1995, with permission from Elsevier.

“Our hypothesis is that xanthomas cause tendons to lose some of their stiffness,” Dr. Scott says. “That means they are more easily stretched, and less efficient in storing and releasing energy. And if stiffness is decreased, they may be more prone to rupturing.”

To test that theory, participants are outfitted with an array of technology. An ultrasound camera is attached to one of their legs to provide dynamic images of the tendon stretching and recoiling. Electrical sensors are placed on each leg to measure muscle-generated force. And reflective markers are affixed to key parts of the body, so that motion-capture cameras mounted to the ceiling can assemble a “stick-figure” video of the person’s movements.

And the treadmill is not your standard gym equipment. It has two separate belts, one for each leg, and each belt sits over a plate that records the force of each footfall.

“It was pretty cool being hooked up to all of those things,” Dagley says.

Building a firmer foundation

All of the data being collected should more firmly establish whether high cholesterol is hurting people’s tendons – a particularly cruel symptom, since exercise is one of the surest means of controlling high cholesterol.

But exercise, if done properly, might also help restore strength to tendons that have been weakened by xanthomas. The key is finding exercises that strengthen the tendon without posing an undue risk of rupturing it. Dr. Scott and Dr. Waugh hope their images and data will provide a firmer foundation for developing such a regimen.

“We believe that exercise sends a signal to injured tissue that realigns cells and collagen, and even produces more collagen,” Dr. Scott says. “We’re not sure if exercise can break up the cholesterol deposits, but my hunch would be we can repair damage to the tendon itself, by making it stiffer.”

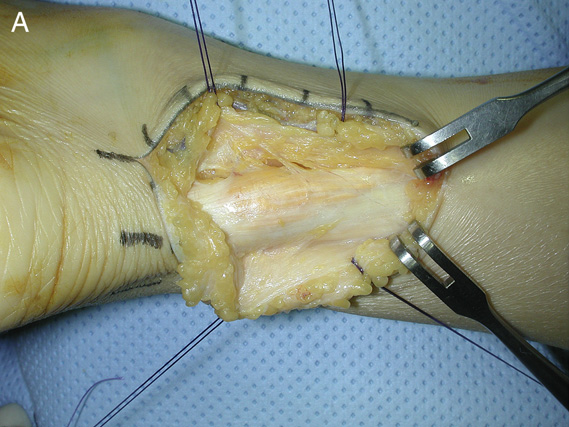

A surgically-exposed tendon xanthoma (yellowish deposits). Reprinted from the Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery, Vol. 50, No. 5, Jae Hoon Ahn et. al., 2011, with permission from Elsevier.

Dr. Scott and Dr. Waugh also hope to make diagnosis less of a hit-or-miss proposition – not only by firmly establishing a link between high cholesterol and weak tendons, but also by showing whether xanthoma-inflicted damage, particularly mild damage, can be picked up by ultrasounds.

Currently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the only reliable way of “seeing” mild xanthomas, but its expense and scarcity make it impractical for diagnosing xanthomas. Ultrasound machines, in contrast, are the part of many general practitioners’ and diagnostic companies’ toolkits.

So each participant, in addition to hitting the treadmill, also submits to a more relaxing form of data collection – lying face down on an examination table while a research assistant scans their Achilles tendons with an ultrasound machine.

“We’re starting to identify features in the Achilles tendon that we see on the ultrasound, and if we can describe those features with enough specificity, that would be really helpful for physicians in diagnosing the condition – and perhaps, diagnosing inherited high cholesterol, which is a ticking time bomb,” Dr. Scott says.