Scientists at the University of British Columbia and Vancouver Coastal Health have proven that multiple sclerosis (MS) can be caused by a single genetic mutation – a rare alteration in DNA that makes it very likely a person will develop the more devastating form of the neurological disease.

The mutation was found in two Canadian families that had several members diagnosed with a rapidly progressive type of MS, in which a person’s symptoms steadily worsen and for which there is no effective treatment.

The discovery of this mutation should erase doubts that at least some forms of MS are inherited.

“This mutation puts these people at the edge of a cliff, but something still has to give them the push to set the disease process in motion,” said senior author Carles Vilarino-Guell, an assistant professor of medical genetics and a member of the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health.

The findings, published today in the journal Neuron, could point the way toward therapies that act upon the gene itself or counteract the mutation’s downstream effects. More immediately, screening for the mutation in high-risk individuals could enable earlier diagnosis and treatment before outward symptoms appear.

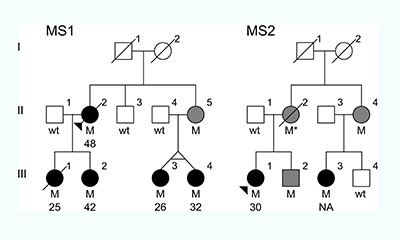

The family trees of the two families that carried the MS-causing mutation. “M”=individuals with the mutation. Black circles=individuals with progressive MS and the age of disease onset. Gray circles or squares=individuals with the mutation whose health is unknown.

MS results from the body’s immune system attacking myelin, the fatty material that insulates neurons and enables rapid transmission of electrical signals. When myelin is damaged, communication between the brain and other parts of the body is disrupted, leading to vision problems, muscle weakness, difficulty with balance and coordination, and cognitive impairments. Canada has one of the highest rate of MS in the world, for reasons that elude scientists.

Although only one in 1,000 MS patients appears to have this mutation, its discovery helps reveal the biological pathway that leads to the rapidly progressive form of the disease, accounting for about 15 percent of people with MS. The discovery could also provide insight into the more common, fluctuating form of MS, known as “relapsing-remitting,” because in most cases, that disease gradually becomes progressive.

The gene where the mutation was found, called NR1H3, produces a protein known as LXRA, which acts as an on-off switch on other genes. Some of those other genes stop the excessive inflammation that damages myelin or help create new myelin to repair the damage. A team led by Weihong Song, a Professor of Psychiatry, found that the mutation – a substitution of just one nucleotide for another in the DNA – produces a defective LXRA protein that is unable to activate those critical genes.

The families with this mutation had donated to a Canadian-wide collection of blood samples from people with MS, begun in 1993 by co-author A. Dessa Sadovnick, a UBC Professor of Medical Genetics and Neurology. The 20-year project, funded by the MS Society of Canada and the Multiple Sclerosis Scientific Research Foundation, has samples from 4,400 people with MS, plus 8,600 blood relatives – one of the largest such biobanks in the world.

Related story: Denial, doubt, derision… and vindication

A UBC medical geneticist’s struggle to reveal the genetic dimension of multiple sclerosis

Read more

Dr. Vilarino-Guell and his collaborators are now awaiting delivery of the first mice to be genetically engineered with this mutation, enabling examination of the cascade of reactions that leads to MS. Currently, scientists simulate MS in mice by either injecting them with myelin, which triggers an immune response, or by feeding them a drug that destroys myelin directly. Neither one mimics how the disease originates in humans.

“If the mice with this mutation develop MS-like symptoms, it’s likely resulting from the same biological pathway as in humans,” Dr. Sadovnick says. “Then we’ll have a much more realistic model for developing and testing drugs to treat progressive MS – drugs we presently don’t have.”

The findings also could lead to more immediate consequences in MS treatment. People with a family history of MS could be screened for this mutation, and if they carry it, could be candidates for early diagnostic imaging long before symptoms appear; or they could opt to increase their intake of Vitamin D (low levels of which have been associated with the disease). If someone diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS were found to have this mutation, they might be candidates for earlier, more aggressive treatment to delay the onset of the progressive form of the disease.

“If you have this gene, chances are you will develop MS and rapidly deteriorate,” said co-author Anthony Traboulsee, the MS Society of Canada Research Chair at UBC and Director of Vancouver Coastal Health’s MS and Neuromyelitis Optica Clinic. “This could give us a critical early window of opportunity to throw everything at the disease, to try to stop it or slow it. Until now, we didn’t have much basis for doing that.”