Chuck Fipke expected nothing but the usual cheer and festivity at the Christmas party he held a few years ago for friends and business associates in Kelowna. But that year’s gathering was marred by some disturbing news from one of his guests, Brad Bennett.

Fipke, who has made his fortune discovering diamonds in Canada, asked about his longtime friend, Brad’s father, Bill Bennett. He expected to hear that the elder Bennett, the Premier of British Columbia from 1975 to 1986, was enjoying retirement after a long and storied career in politics.

Instead, Bennett said his father had fallen victim to Alzheimer’s disease.

Fipke was stunned. Not only was it difficult for him to fathom that a man so vibrant and forceful was gradually diminishing with dementia. He also realized why, several years before, Bill Bennett himself had suggested that Fipke, a UBC alumnus, support Alzheimer’s research at his alma mater.

“I was interested, and I was going to do it, but this comes up and that comes up,” Fipke says. “I was so disappointed in myself to have not donated when I should have. I got to thinking about it, and thought, ‘Ronald Reagan got it, Margaret Thatcher got it. Now Bill Bennett.’ All these very smart people who mean so much to the world. We really need to solve this problem – put an end to it.”

“Chuck has given us a voice”

From that moment, Fipke resolved to follow through on that suggestion. The result: Three gifts, totaling $9.1 million, for Alzheimer’s research at UBC.

Fipke gave $3 million to endow a professorship dedicated to Alzheimer’s research, now held by Haakon Nygaard, a neurologist recruited from the Yale School of Medicine. He pledged $600,000 to outfit Dr. Nygaard’s lab with cutting-edge equipment. And he committed another $5.5 million to support the purchase of a machine that combines positron emission tomography (PET) with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – the most novel and coveted brain imaging technolog y available, capable of spotting subtle changes in brain chemistry and structure a decade or more before symptoms appear.

The gifts were announced at a ceremony in September at the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health, where Brad Bennett publicly acknowledged his father’s illness for the first time.

“My father, as you know, was a person of high intellect, great drive, and those qualities aren’t there anymore,” Bennett, the former Chair of UBC’s Board of Governors, told invited guests, reporters, television crews and photographers. “We, by nature… are private individuals, who like to keep our private life our private life, and up to now we’ve chosen to do that with respect to my father’s condition.

“But Chuck has given us a voice, and for very good reason. Hopefully this donation and our presence here today will inspire other families facing the same situation to feel that it’s OK to talk about it… to help find further treatments and eventually a cure for Alzheimer’s, all forms of dementia and related brain diseases.”

Not easily intimidated

A geologist, prospector and entrepreneur, Fipke’s donation ref lects his lifelong passion for exploration.

After graduating from UBC with a bachelor’s degree in geolog y, he traveled the world for various mining companies, and opened his own lab in Kelowna, becoming an expert on “indicator minerals” that signal the presence of diamonds.

Later, he struck out on his own, spending weeks near the Arctic Circle before finding high concentrations of diamonds at Lac de Gras, in the Northwest Territories, in 1991. With a corporate partner, he established the Ekati Mine, the first commercial diamond mine in North America – thus jump-starting the Canadian diamond industry, which in 2011 accounted for 18 per cent of the world’s rough diamond production by value.

“It’s no wonder that he chose to devote some of his resources to a challenge as formidable as Alzheimer’s disease,” said Gavin Stuart, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and UBC’s Vice Provost, Health. “Chuck, I’ve come to learn, is not easily intimidated – not by competition from global corporations, not by the harshness of the Arctic climate and its rugged landscape, and certainly not by conventional wisdom. We probably need more Chuck Fipkes in our labs and clinics.”

Instead, Fipke has enabled UBC to recruit Dr. Nygaard, one of North America’s most promising young neuroscientists, and a specialist in treating patients with Alzheimer’s.

Dr. Nygaard spent the past decade at Yale – first as a neurolog y resident, then as a PhD student, and finally as a faculty member. His interest in Alzheimer’s disease was sparked as a medical student in Nebraska, during a rotation with a physician who saw many patients with the disease.

As a doctoral student, he studied connections between epilepsy and Alzheimer’s, and as a faculty member, he was the founding Co-Director of Yale’s Memory Disorders Clinic.

Re-purposing a cancer drug

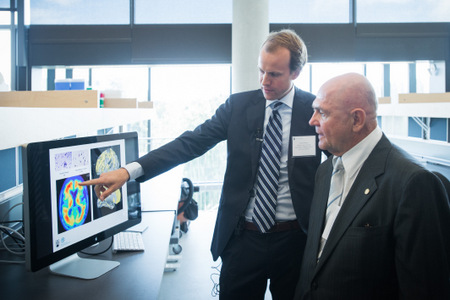

L-R: Haakon Nygaard, the Fipke Professor in Alzheimer’s Research, in his lab, describes the biology of the neurodegenerative disease to donor Chuck Fipke. Photo credit: Martin Dee

Dr. Nygaard, who arrived at UBC in July, is off to a strong start.

He will be co-leading an $11 million study funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health examining whether saracatinib, a drug developed for cancer, can curb the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. He and his collaborators at Yale completed the first phase in Connecticut in early 2014, demonstrating the drug’s short-term safety. The next phase will aim to show, using PET, that the drug can arrest an Alzheimer’s-specific decline in metabolic activity in certain parts of the brain. The trial will enroll 152 patients at as many as 20 sites, including Vancouver.

Dr. Nygaard, who will be seeing dementia patients at the Centre for Brain Health (a partnership with Vancouver Coastal Health), also plans to collect DNA samples of cognitively healthy people over 100 years old, searching for shared genetic characteristics that might distinguish them from people who develop dementia.

In addition, Dr. Nygaard will continue work on a theory he pursued in his Yale dissertation: that Alzheimer’s disease might result from neurological hyperactivity. Since epilepsy is the most extreme form of such hyperactivity, he will study the potential of anti-convulsant drugs to delay or reverse Alzheimer’s disease.

Most of all, Dr. Nygaard will be striving to speed the process of converting research findings into treatments, especially now that pharmaceutical companies – discouraged by poor results in several large trials – are starting to retreat from the neurological realm, and Alzheimer’s in particular. He believes that he and his colleagues will follow Fipke’s example.

“Nobody believed Chuck when he insisted on the existence of diamonds in Canada,” Dr. Nygaard said. “But Chuck persevered, and as you know, the rest is history… That’s a very similar to the situation we’re facing now with Alzheimer’s disease… Here at UBC, the words ‘giving up’ have not entered the conversation. In fact, in many ways, I think we’re just getting started.”